| Title: | Power Analysis for Differential Expression Studies |

| Version: | 2026.1.30 |

| Description: | Provides a convenient framework to simulate, test, power, and visualize data for differential expression studies with lognormal or negative binomial outcomes. Supported designs are two-sample comparisons of independent or dependent outcomes. Power may be summarized in the context of controlling the per-family error rate or family-wise error rate. Negative binomial methods are described in Yu, Fernandez, and Brock (2017) <doi:10.1186/s12859-017-1648-2> and Yu, Fernandez, and Brock (2020) <doi:10.1186/s12859-020-3541-7>. |

| URL: | https://brettklamer.com/work/depower/, https://bitbucket.org/bklamer/depower/ |

| License: | MIT + file LICENSE |

| Depends: | R (≥ 4.2.0) |

| Imports: | Rdpack, stats, mvnfast, glmmTMB, dplyr, multidplyr, ggplot2, scales |

| Suggests: | tinytest, rmarkdown |

| RdMacros: | Rdpack |

| Language: | en-US |

| Encoding: | UTF-8 |

| RoxygenNote: | 7.3.3 |

| NeedsCompilation: | no |

| Packaged: | 2026-01-30 18:27:27 UTC; x |

| Author: | Brett Klamer |

| Maintainer: | Brett Klamer <code@brettklamer.com> |

| Repository: | CRAN |

| Date/Publication: | 2026-01-30 18:50:02 UTC |

depower: Power Analysis for Differential Expression Studies

Description

Provides a convenient framework to simulate, test, power, and visualize data for differential expression studies with lognormal or negative binomial outcomes. Supported designs are two-sample comparisons of independent or dependent outcomes. Power may be summarized in the context of controlling the per-family error rate or family-wise error rate. Negative binomial methods are described in Yu, Fernandez, and Brock (2017) doi:10.1186/s12859-017-1648-2 and Yu, Fernandez, and Brock (2020) doi:10.1186/s12859-020-3541-7.

Author(s)

Maintainer: Brett Klamer code@brettklamer.com (ORCID)

Authors:

Lianbo Yu lianbo.yu@osumc.edu (ORCID)

See Also

Useful links:

Add confidence intervals for power estimates

Description

Calculates and adds confidence intervals for power estimates to objects returned by power().

The confidence interval quantifies uncertainty about the true power parameter.

Usage

add_power_ci(x, ci_level = 0.95, method = c("wilson", "exact"))

Arguments

x |

(data.frame) |

ci_level |

(Scalar numeric: |

method |

(Scalar character: |

Details

Power estimation via simulation is a binomial proportion problem. The confidence interval answers: "What is the plausible range of true power values given my simulation results?"

Let \pi denote the true power value, \hat{\pi} = x/n denote the observed power value, n denote the number of simulations, and x = \text{round}(\hat{\pi} \cdot n) denote the number of rejections.

Two methods are available.

Wilson Score Interval

The Wilson score interval is derived from inverting the score test. Starting with the inequality

\left| \frac{\hat{\pi}-\pi}{\sqrt{\pi(1-\pi)/n}} \right| \le z_{1-\alpha/2},

and solving the resulting quadratic for \pi yields

\frac{\hat{\pi}+\frac{z^2}{2n} \pm z \sqrt{\frac{\hat{\pi}(1-\hat{\pi})}{n}+\frac{z^2}{4n^2}}}{1+\frac{z^2}{n}},

with z = z_{1-\alpha/2} and \hat{\pi} = x/n.

Clopper-Pearson Interval

The Clopper-Pearson exact interval inverts the binomial test via Beta quantiles.

The bounds (\pi_L, \pi_U) satisfy:

P(X \geq x \mid \pi = \pi_L) = \alpha/2

P(X \leq x \mid \pi = \pi_U) = \alpha/2

With x successes in n trials,

\pi_L = B^{-1}\left(\frac{\alpha}{2}; x, n-x+1\right)

\pi_U = B^{-1}\left(1-\frac{\alpha}{2}; x+1, n-x\right)

where B^{-1}(q; a, b) is the q-th quantile of

\text{Beta}(a, b).

This method guarantees at least nominal coverage but is conservative (intervals are wider than necessary).

Approximate parametric tests

When power is computed using approximate parametric tests (see simulated()), the power estimate and confidence/prediction intervals apply to the Monte Carlo test power \mu_K = P(\hat{p} \leq \alpha) rather than the exact test power \pi = P(p \leq \alpha).

These quantities converge as the number of datasets simulated under the null hypothesis K increases.

The minimum observable p-value is 1/(K+1), so K > 1/\alpha - 1 is required to observe any rejections.

For practical accuracy, we recommend choosing \text{max}(5000, K \gg 1/\alpha - 1) for most scenarios.

For example, if \alpha = 0.05, use simulated(nsims = 5000).

Value

The input data frame with additional columns:

| Name | Description |

power_ci_lower | Lower bound of confidence interval. |

power_ci_upper | Upper bound of confidence interval. |

and added attribute "ci_info" containing the method description, method name and confidence level.

References

Newcombe RG (1998). “Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods.” Statistics in Medicine, 17(8), 857–872. ISSN 0277-6715, 1097-0258, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::AID-SIM777>3.0.CO;2-E.,

Wilson EB (1927). “Probable Inference, the Law of Succession, and Statistical Inference.” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 22(158), 209–212. ISSN 0162-1459, 1537-274X, doi:10.1080/01621459.1927.10502953.,

Clopper CJ, Pearson ES (1934). “THE USE OF CONFIDENCE OR FIDUCIAL LIMITS ILLUSTRATED IN THE CASE OF THE BINOMIAL.” Biometrika, 26(4), 404–413. ISSN 0006-3444, 1464-3510, doi:10.1093/biomet/26.4.404.

See Also

power(),

eval_power_ci(),

add_power_pi()

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# add_power_ci() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

x <- sim_nb(

n1 = 10,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = c(1.4, 1.6),

dispersion1 = 2,

nsims = 200

) |>

power(wald_test_nb())

# Compare methods

add_power_ci(x, method = "wilson")

add_power_ci(x, method = "exact")

# 99% confidence interval

add_power_ci(x, ci_level = 0.99)

# Plot with shaded region for confidence interval of the power estimate.

add_power_ci(x) |>

plot()

Add Bayesian posterior predictive intervals for power estimates

Description

Calculates and adds Bayesian posterior predictive intervals for power estimates in objects returned by power().

The posterior predictive interval quantifies the expected range of power estimates from a future simulation study.

Usage

add_power_pi(x, future_nsims = NULL, pi_level = 0.95, prior = c(1, 1))

Arguments

x |

(data.frame) |

future_nsims |

(Scalar integer or |

pi_level |

(Scalar numeric: |

prior |

(Numeric vector of length 2: |

Details

Power estimation via simulation is a binomial proportion problem.

The posterior predictive interval answers: "If I run a new simulation study with m simulations, what range of power estimates might I observe?"

Let \pi denote the true power value, \hat{\pi} = x/n denote the observed power value, n denote the number of simulations, and x = \text{round}(\hat{\pi} \cdot n) denote the number of rejections.

With a \text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta) prior on the true power \pi, the posterior after observing x successes in n trials is:

\pi \mid X = x \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha + x, \beta + n - x).

The posterior predictive distribution for Y, the number of successes in a future study with m trials, is Beta-Binomial:

Y \mid X = x \sim \text{BetaBinomial}(m, \alpha + x, \beta + n - x).

The posterior predictive interval is constructed from quantiles of this distribution, expressed as proportions Y/m.

The posterior predictive mean and variance of \hat{\pi}_{\text{new}} = Y/m are:

\begin{aligned}

E[\hat{\pi}_{\text{new}} \mid X = x] &= \frac{\alpha + x}{\alpha + \beta + n} \\

\text{Var}[\hat{\pi}_{\text{new}} \mid X = x]

&= \frac

{(\alpha + x)(\beta + n - x)(\alpha + \beta + n + m)}

{m (\alpha + \beta + n)^{2} (\alpha + \beta + n + 1)}.

\end{aligned}

Argument future_nsims

The argument future_nsims allows you to estimate prediction interval bounds for a hypothetical future study with different number of simulations.

Note that a small initial number for nsims results in substantial uncertainty about the true power.

A correspondingly large number of future simulations future_nsims will more precisely estimate the true power, but the past large uncertainty is still carried forward.

Therefore you still need an adequate number of simulations nsims in the original study, not just more in the replication future_nsims, to ensure narrow prediction intervals.

Approximate parametric tests

When power is computed using approximate parametric tests (see simulated()), the power estimate and confidence/prediction intervals apply to the Monte Carlo test power \mu_K = P(\hat{p} \leq \alpha) rather than the exact test power \pi = P(p \leq \alpha).

These quantities converge as the number of datasets simulated under the null hypothesis K increases.

The minimum observable p-value is 1/(K+1), so K > 1/\alpha - 1 is required to observe any rejections.

For practical accuracy, we recommend choosing \text{max}(5000, K \gg 1/\alpha - 1) for most scenarios.

For example, if \alpha = 0.05, use simulated(nsims = 5000).

Value

The input data frame with additional columns:

| Name | Description |

power_pi_mean | Predictive mean of future power estimate. |

power_pi_lower | Lower bound of posterior predictive interval. |

power_pi_upper | Upper bound of posterior predictive interval. |

and added attribute "pi_info" containing the method description, method name, level, prior values, and future simulation count.

References

Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB (2013). Bayesian data analysis, Texts in statistical science series, Third edition edition. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 9781439840955.

See Also

power(),

eval_power_pi(),

add_power_ci()

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# add_power_pi() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

x <- sim_nb(

n1 = 10,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = c(1.4, 1.6),

dispersion1 = 2,

nsims = 200

) |>

power(wald_test_nb())

# Add posterior predictive intervals

# default: predict for same number of simulations

add_power_pi(x)

# Compare posterior predictive interval width across different future

# study sizes

add_power_pi(x, future_nsims = 100) # wider

add_power_pi(x, future_nsims = 1000) # narrower

# Use Jeffreys prior instead of uniform

add_power_pi(x, prior = c(0.5, 0.5))

# Plot with shaded region for prediction interval of the power estimate.

add_power_pi(x) |>

plot()

Test statistic distribution under the null

Description

Constructs a list which defines the test statistic reference distribution under the null hypothesis.

Usage

asymptotic()

simulated(method = "approximate", nsims = 1000L, ncores = 1L, ...)

Arguments

method |

(Scalar string: |

nsims |

(Scalar integer: |

ncores |

(Scalar integer: |

... |

Optional arguments for internal use. |

Details

The default asymptotic test is performed for distribution = asymptotic().

When setting argument distribution = simulated(method = "exact"), the

exact randomization test is defined by:

Independent two-sample tests

Calculate the observed test statistic.

Check if

length(combn(x=n1+n2, m=n1))<1e6If

TRUEcontinue with the exact randomization test.If

FALSErevert to the approximate randomization test.

For all

combn(x=n1+n2, m=n1)permutations:Assign corresponding group labels.

Calculate the test statistic.

Calculate the exact randomization test p-value as the mean of the logical vector

resampled_test_stats >= observed_test_stat.

Dependent two-sample tests

Calculate the observed test statistic.

Check if

npairs < 21(maximum 2^20 resamples)If

TRUEcontinue with the exact randomization test.If

FALSErevert to the approximate randomization test.

For all

2^npairspermutations:Assign corresponding pair labels.

Calculate the test statistic.

Calculate the exact randomization test p-value as the mean of the logical vector

resampled_test_stats >= observed_test_stat.

For argument distribution = simulated(method = "approximate"), the

approximate randomization test is defined by:

Independent two-sample tests

Calculate the observed test statistic.

For

nsimsiterations:Randomly assign group labels.

Calculate the test statistic.

Insert the observed test statistic to the vector of resampled test statistics.

Calculate the approximate randomization test p-value as the mean of the logical vector

resampled_test_stats >= observed_test_stat.

Dependent two-sample tests

Calculate the observed test statistic.

For

nsimsiterations:Randomly assign pair labels.

Calculate the test statistic.

Insert the observed test statistic to the vector of resampled test statistics.

Calculate the approximate randomization test p-value as the mean of the logical vector

resampled_test_stats >= observed_test_stat.

In the power analysis setting, power(), we can simulate data for

groups 1 and 2 using their known distributions under the assumptions of the

null hypothesis. Unlike above where nonparametric randomization tests

are performed, in this setting approximate parametric tests are performed.

For example, power(wald_test_nb(distribution = simulated())) would result

in an approximate parametric Wald test defined by:

For each relevant design row in

data:For

simulated(nsims=integer())iterations:Simulate new data for group 1 and group 2 under the null hypothesis.

Calculate the Wald test statistic,

\chi^2_{null}.

Collect all

\chi^2_{null}into a vector.For each of the

sim_nb(nsims=integer())simulated datasets:Calculate the Wald test statistic,

\chi^2_{obs}.Calculate the p-value based on the empirical null distribution of test statistics,

\chi^2_{null}. (the mean of the logical vectornull_test_stats >= observed_test_stat)

Collect all p-values into a vector.

Calculate power as

sum(p <= alpha) / nsims.

Return all results from

power().

Randomization tests use the positive-biased p-value estimate in the style of Davison and Hinkley (1997) (see also Phipson and Smyth (2010)):

\hat{p} = \frac{1 + \sum_{i=1}^B \mathbb{I} \{\chi^2_i \geq \chi^2_{obs}\}}{B + 1}.

The number of resamples defines the minimum observable p-value

(e.g. nsims=1000L results in min(p-value)=1/1001).

It's recommended to set \text{nsims} \gg \frac{1}{\alpha}.

Value

list

References

Davison AC, Hinkley DV (1997). Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 1 edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521574716, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511802843.

Phipson B, Smyth GK (2010). “Permutation P-values Should Never Be Zero: Calculating Exact P-values When Permutations Are Randomly Drawn.” Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology, 9(1). ISSN 1544-6115, doi:10.48550/arXiv.1603.05766.

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# asymptotic() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

data <- sim_nb(

n1 = 60,

n2 = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.5,

dispersion1 = 2,

dispersion2 = 8

)

data |>

wald_test_nb(distribution = asymptotic())

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# simulated() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

data |>

wald_test_nb(distribution = simulated(nsims = 200L))

Evaluate confidence intervals for power estimates

Description

Calculates the confidence interval for a power estimate from a simulation study. The confidence interval quantifies uncertainty about the true power parameter.

When the number of simulations used to calculate a test's power is too small, the power estimate will have high uncertainty (wide confidence/prediction intervals). When the number of simulations used to calculate a test's power is too large, computational time may be prohibitive. This function allows you to determine the appropriate number of simulated datasets to reach your desired precision for power before spending computational time on simulations.

Usage

eval_power_ci(power, nsims, ci_level = 0.95, method = c("wilson", "exact"))

Arguments

power |

(numeric: |

nsims |

(integer: |

ci_level |

(Scalar numeric: |

method |

(Scalar character: |

Details

Power estimation via simulation is a binomial proportion problem. The confidence interval answers: "What is the plausible range of true power values given my simulation results?"

Let \pi denote the hypothetical true power value, \hat{\pi} = x/n denote the hypothetical observed power value, n denote the number of simulations, and x = \text{round}(\hat{\pi} \cdot n) denote the number of rejections.

Two methods are available.

Wilson Score Interval

The Wilson score interval is derived from inverting the score test. Starting with the inequality

\left| \frac{\hat{\pi}-\pi}{\sqrt{\pi(1-\pi)/n}} \right| \le z_{1-\alpha/2},

and solving the resulting quadratic for \pi yields

\frac{\hat{\pi}+\frac{z^2}{2n} \pm z \sqrt{\frac{\hat{\pi}(1-\hat{\pi})}{n}+\frac{z^2}{4n^2}}}{1+\frac{z^2}{n}},

with z = z_{1-\alpha/2} and \hat{\pi} = x/n.

Clopper-Pearson Interval

The Clopper-Pearson exact interval inverts the binomial test via Beta quantiles.

The bounds (\pi_L, \pi_U) satisfy:

P(X \geq x \mid \pi = \pi_L) = \alpha/2

P(X \leq x \mid \pi = \pi_U) = \alpha/2

With x successes in n trials,

\pi_L = B^{-1}\left(\frac{\alpha}{2}; x, n-x+1\right)

\pi_U = B^{-1}\left(1-\frac{\alpha}{2}; x+1, n-x\right)

where B^{-1}(q; a, b) is the q-th quantile of

\text{Beta}(a, b).

This method guarantees at least nominal coverage but is conservative (intervals are wider than necessary).

Approximate parametric tests

When power is computed using approximate parametric tests (see simulated()), the power estimate and confidence/prediction intervals apply to the Monte Carlo test power \mu_K = P(\hat{p} \leq \alpha) rather than the exact test power \pi = P(p \leq \alpha).

These quantities converge as the number of datasets simulated under the null hypothesis K increases.

The minimum observable p-value is 1/(K+1), so K > 1/\alpha - 1 is required to observe any rejections.

For practical accuracy, we recommend choosing \text{max}(5000, K \gg 1/\alpha - 1) for most scenarios.

For example, if \alpha = 0.05, use simulated(nsims = 5000).

Value

A list with elements:

| Name | Description |

lower | Lower bound of confidence interval. |

upper | Upper bound of confidence interval. |

References

Newcombe RG (1998). “Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods.” Statistics in Medicine, 17(8), 857–872. ISSN 0277-6715, 1097-0258, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::AID-SIM777>3.0.CO;2-E.,

Wilson EB (1927). “Probable Inference, the Law of Succession, and Statistical Inference.” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 22(158), 209–212. ISSN 0162-1459, 1537-274X, doi:10.1080/01621459.1927.10502953.,

Clopper CJ, Pearson ES (1934). “THE USE OF CONFIDENCE OR FIDUCIAL LIMITS ILLUSTRATED IN THE CASE OF THE BINOMIAL.” Biometrika, 26(4), 404–413. ISSN 0006-3444, 1464-3510, doi:10.1093/biomet/26.4.404.

See Also

add_power_ci(),

eval_power_pi()

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# eval_power_ci() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

# Expected CI for 80% power with 1000 simulations

eval_power_ci(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000)

# Compare precision across different simulation counts

eval_power_ci(power = 0.80, nsims = c(100, 500, 1000, 5000))

# Compare Wilson vs exact method

eval_power_ci(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000, method = "wilson")

eval_power_ci(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000, method = "exact")

# Vectorized over power values

eval_power_ci(power = c(0.70, 0.80, 0.90), nsims = 1000)

# 99% confidence interval

eval_power_ci(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000, ci_level = 0.99)

Evaluate Bayesian posterior predictive intervals for power estimates

Description

Calculates the Bayesian posterior predictive interval for a power estimate from a simulation study. The posterior predictive interval quantifies the expected range of power estimates from a future simulation study.

When the number of simulations used to calculate a test's power is too small, the power estimate will have high uncertainty (wide confidence/prediction intervals). When the number of simulations used to calculate a test's power is too large, computational time may be prohibitive. This function allows you to determine the appropriate number of simulated datasets to reach your desired precision for power before spending computational time on simulations.

Usage

eval_power_pi(

power,

nsims,

future_nsims = NULL,

pi_level = 0.95,

prior = c(1, 1)

)

Arguments

power |

(numeric: |

nsims |

(integer: |

future_nsims |

(integer or |

pi_level |

(Scalar numeric: |

prior |

(numeric vector of length 2: |

Details

Power estimation via simulation is a binomial proportion problem.

The posterior predictive interval answers: "If I run a new simulation study with m simulations, what range of power estimates might I observe?"

Let \pi denote the hypothetical true power value, \hat{\pi} = x/n denote the hypothetical observed power value, n denote the number of simulations, and x = \text{round}(\hat{\pi} \cdot n) denote the number of rejections.

With a \text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta) prior on the true power \pi, the posterior after observing x successes in n trials is:

\pi \mid X = x \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha + x, \beta + n - x).

The posterior predictive distribution for Y, the number of successes in a future study with m trials, is Beta-Binomial:

Y \mid X = x \sim \text{BetaBinomial}(m, \alpha + x, \beta + n - x).

The posterior predictive interval is constructed from quantiles of this distribution, expressed as proportions Y/m.

The posterior predictive mean and variance of \hat{\pi}_{\text{new}} = Y/m are:

\begin{aligned}

E[\hat{\pi}_{\text{new}} \mid X = x] &= \frac{\alpha + x}{\alpha + \beta + n} \\

\text{Var}[\hat{\pi}_{\text{new}} \mid X = x]

&= \frac

{(\alpha + x)(\beta + n - x)(\alpha + \beta + n + m)}

{m (\alpha + \beta + n)^{2} (\alpha + \beta + n + 1)}.

\end{aligned}

Argument future_nsims

The argument future_nsims allows you to estimate prediction interval bounds for a hypothetical future study with different number of simulations.

Note that a small initial number for nsims results in substantial uncertainty about the true power.

A correspondingly large number of future simulations future_nsims will more precisely estimate the true power, but the past large uncertainty is still carried forward.

Therefore you still need an adequate number of simulations nsims in the original study, not just more in the replication future_nsims, to ensure narrow prediction intervals.

Approximate parametric tests

When power is computed using approximate parametric tests (see simulated()), the power estimate and confidence/prediction intervals apply to the Monte Carlo test power \mu_K = P(\hat{p} \leq \alpha) rather than the exact test power \pi = P(p \leq \alpha).

These quantities converge as the number of datasets simulated under the null hypothesis K increases.

The minimum observable p-value is 1/(K+1), so K > 1/\alpha - 1 is required to observe any rejections.

For practical accuracy, we recommend choosing \text{max}(5000, K \gg 1/\alpha - 1) for most scenarios.

For example, if \alpha = 0.05, use simulated(nsims = 5000).

Value

A list with elements:

| Name | Description |

mean | Predictive mean of future power estimate. |

lower | Lower bound of posterior predictive interval. |

upper | Upper bound of posterior predictive interval. |

References

Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB (2013). Bayesian data analysis, Texts in statistical science series, Third edition edition. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 9781439840955.

See Also

add_power_pi(),

eval_power_ci()

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# eval_power_pi() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

# Expected PI for 80% power with 1000 simulations

eval_power_pi(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000)

# Compare precision across different simulation counts

eval_power_pi(power = 0.80, nsims = c(100, 500, 1000, 5000))

# Predict for a larger future study (narrower interval)

eval_power_pi(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000, future_nsims = 5000)

# Predict for a smaller future study (wider interval)

eval_power_pi(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000, future_nsims = 100)

# Vectorized over power values

eval_power_pi(power = c(0.70, 0.80, 0.90), nsims = 1000)

# Use Jeffreys prior instead of uniform

eval_power_pi(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000, prior = c(0.5, 0.5))

# 99% predictive interval

eval_power_pi(power = 0.80, nsims = 1000, pi_level = 0.99)

GLM for NB ratio of means

Description

Generalized linear model for two independent negative binomial outcomes.

Usage

glm_nb(data, equal_dispersion = FALSE, test = "wald", ci_level = NULL, ...)

Arguments

data |

(list) |

equal_dispersion |

(Scalar logical: |

test |

(String: |

ci_level |

(Scalar numeric: |

... |

Optional arguments passed to |

Details

Uses glmmTMB::glmmTMB() in the form

glmmTMB( formula = value ~ condition, data = data, dispformula = ~ condition, family = nbinom2 )

to model independent negative binomial outcomes

X_1 \sim \text{NB}(\mu, \theta_1) and X_2 \sim \text{NB}(r\mu, \theta_2)

where \mu is the mean of group 1, r is the ratio of the means of

group 2 with respect to group 1, \theta_1 is the dispersion parameter

of group 1, and \theta_2 is the dispersion parameter of group 2.

The hypotheses for the LRT and Wald test of r are

\begin{aligned}

H_{null} &: log(r) = 0 \\

H_{alt} &: log(r) \neq 0

\end{aligned}

where r = \frac{\bar{X}_2}{\bar{X}_1} is the population ratio of

arithmetic means for group 2 with respect to group 1 and

log(r_{null}) = 0 assumes the population means are identical.

Value

A list with the following elements:

| Slot | Subslot | Name | Description |

| 1 | chisq | \chi^2 test statistic for the ratio of means. |

|

| 2 | df | Degrees of freedom. | |

| 3 | p | p-value. | |

| 4 | ratio | Estimated ratio of means (group 2 / group 1). | |

| 4 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 4 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 4 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 5 | mean1 | Estimated mean of group 1. | |

| 5 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 5 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 5 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 6 | mean2 | Estimated mean of group 2. | |

| 6 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 6 | 2 | lower | Wald confidence interval lower bound. |

| 6 | 3 | upper | Wald confidence interval upper bound. |

| 7 | dispersion1 | Estimated dispersion of group 1. | |

| 7 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 7 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 7 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 8 | dispersion2 | Estimated dispersion of group 2. | |

| 8 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 8 | 2 | lower | Wald confidence interval lower bound. |

| 8 | 3 | upper | Wald confidence interval upper bound. |

| 9 | n1 | Sample size of group 1. | |

| 10 | n2 | Sample size of group 2. | |

| 11 | method | Method used for the results. | |

| 12 | test | Type of hypothesis test. | |

| 13 | alternative | The alternative hypothesis. | |

| 14 | equal_dispersion | Whether or not equal dispersions were assumed. | |

| 15 | ci_level | Confidence level of the intervals. | |

| 16 | hessian | Information about the Hessian matrix. | |

| 17 | convergence | Information about convergence. |

References

Hilbe JM (2011). Negative Binomial Regression, 2 edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521198158 9780511973420, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511973420.

Hilbe JM (2014). Modeling count data. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. ISBN 9781107028333 9781107611252, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139236065.

See Also

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# glm_nb() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

d <- sim_nb(

n1 = 60,

n2 = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.5,

dispersion1 = 2,

dispersion2 = 8

)

lrt <- glm_nb(d, equal_dispersion = FALSE, test = "lrt", ci_level = 0.95)

lrt

wald <- glm_nb(d, equal_dispersion = FALSE, test = "wald", ci_level = 0.95)

wald

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Compare results to manual calculation of chi-square statistic

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Use the same data, but as a data frame instead of list

set.seed(1234)

df <- sim_nb(

n1 = 60,

n2 = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.5,

dispersion1 = 2,

dispersion2 = 8,

return_type = "data.frame"

)

mod_alt <- glmmTMB::glmmTMB(

formula = value ~ condition,

data = df,

dispformula = ~ condition,

family = glmmTMB::nbinom2

)

mod_null <- glmmTMB::glmmTMB(

formula = value ~ 1,

data = df,

dispformula = ~ condition,

family = glmmTMB::nbinom2

)

lrt_chisq <- as.numeric(-2 * (logLik(mod_null) - logLik(mod_alt)))

lrt_chisq

wald_chisq <- summary(mod_alt)$coefficients$cond["condition2", "z value"]^2

wald_chisq

anova(mod_null, mod_alt)

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Compare results to wald_test_nb()

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

wald2 <- wald_test_nb(d, equal_dispersion = FALSE, ci_level = 0.95)

all.equal(wald$chisq, wald2$chisq, tolerance = 0.01)

GLMM for BNB ratio of means

Description

Generalized linear mixed model for bivariate negative binomial outcomes.

Usage

glmm_bnb(data, test = "wald", ci_level = NULL, ...)

Arguments

data |

(list) |

test |

(String: |

ci_level |

(Scalar numeric: |

... |

Optional arguments passed to |

Details

Uses glmmTMB::glmmTMB() in the form

glmmTMB( formula = value ~ condition + (1 | item), data = data, dispformula = ~ 1, family = nbinom2 )

to model dependent negative binomial outcomes

X_1, X_2 \sim \text{BNB}(\mu, r, \theta) where \mu is the mean of

sample 1, r is the ratio of the means of sample 2 with respect to

sample 1, and \theta is the dispersion parameter.

The hypotheses for the LRT and Wald test of r are

\begin{aligned}

H_{null} &: log(r) = 0 \\

H_{alt} &: log(r) \neq 0

\end{aligned}

where r = \frac{\bar{X}_2}{\bar{X}_1} is the population ratio of

arithmetic means for sample 2 with respect to sample 1 and

log(r_{null}) = 0 assumes the population means are identical.

When simulating data from sim_bnb(), the mean is a function of the

item (subject) random effect which in turn is a function of the dispersion

parameter. Thus, glmm_bnb() has biased mean and dispersion estimates. The

bias increases as the dispersion parameter gets smaller and decreases as

the dispersion parameter gets larger. However, estimates of the ratio and

standard deviation of the random intercept tend to be accurate. The p-value

for glmm_bnb() is generally overconservative compared to glmm_poisson(),

wald_test_bnb() and lrt_bnb(). In summary, the negative binomial

mixed-effects model fit by glmm_bnb() is not recommended for the BNB data

simulated by sim_bnb(). Instead, wald_test_bnb() or lrt_bnb() should

typically be used instead.

Value

A list with the following elements:

| Slot | Subslot | Name | Description |

| 1 | chisq | \chi^2 test statistic for the ratio of means. |

|

| 2 | df | Degrees of freedom. | |

| 3 | p | p-value. | |

| 4 | ratio | Estimated ratio of means (sample 2 / sample 1). | |

| 4 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 4 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 4 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 5 | mean1 | Estimated mean of sample 1. | |

| 5 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 5 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 5 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 6 | mean2 | Estimated mean of sample 2. | |

| 6 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 6 | 2 | lower | Wald confidence interval lower bound. |

| 6 | 3 | upper | Wald confidence interval upper bound. |

| 7 | dispersion | Estimated dispersion. | |

| 7 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 7 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 7 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 8 | item_sd | Estimated standard deviation of the item (subject) random intercept. | |

| 8 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 8 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 8 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 9 | n1 | Sample size of sample 1. | |

| 10 | n2 | Sample size of sample 2. | |

| 11 | method | Method used for the results. | |

| 12 | test | Type of hypothesis test. | |

| 13 | alternative | The alternative hypothesis. | |

| 14 | ci_level | Confidence level of the interval. | |

| 15 | hessian | Information about the Hessian matrix. | |

| 16 | convergence | Information about convergence. |

References

Hilbe JM (2011). Negative Binomial Regression, 2 edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521198158 9780511973420, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511973420.

Hilbe JM (2014). Modeling count data. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. ISBN 9781107028333 9781107611252, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139236065.

See Also

wald_test_bnb(),

lrt_bnb(),

glmm_poisson()

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# glmm_bnb() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

d <- sim_bnb(

n = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.2,

dispersion = 2

)

lrt <- glmm_bnb(d, test = "lrt")

lrt

wald <- glmm_bnb(d, test = "wald", ci_level = 0.95)

wald

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Compare results to manual calculation of chi-square statistic

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Use the same data, but as a data frame instead of list

set.seed(1234)

d <- sim_bnb(

n = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.2,

dispersion = 2,

return_type = "data.frame"

)

mod_alt <- glmmTMB::glmmTMB(

formula = value ~ condition + (1 | item),

data = d,

dispformula = ~ 1,

family = glmmTMB::nbinom2

)

mod_null <- glmmTMB::glmmTMB(

formula = value ~ 1 + (1 | item),

data = d,

dispformula = ~ 1,

family = glmmTMB::nbinom2

)

lrt_chisq <- as.numeric(-2 * (logLik(mod_null) - logLik(mod_alt)))

lrt_chisq

wald_chisq <- summary(mod_alt)$coefficients$cond["condition2", "z value"]^2

wald_chisq

anova(mod_null, mod_alt)

GLMM for Poisson ratio of means

Description

Generalized linear mixed model for two dependent Poisson outcomes.

Usage

glmm_poisson(data, test = "wald", ci_level = NULL, ...)

Arguments

data |

(list) |

test |

(String: |

ci_level |

(Scalar numeric: |

... |

Optional arguments passed to |

Details

Uses glmmTMB::glmmTMB() in the form

glmmTMB( formula = value ~ condition + (1 | item), data = data, family = stats::poisson )

to model dependent Poisson outcomes X_1 \sim \text{Poisson}(\mu) and

X_2 \sim \text{Poisson}(r \mu) where \mu is the mean of sample 1

and r is the ratio of the means of sample 2 with respect to sample 1.

The hypotheses for the LRT and Wald test of r are

\begin{aligned}

H_{null} &: log(r) = 0 \\

H_{alt} &: log(r) \neq 0

\end{aligned}

where r = \frac{\bar{X}_2}{\bar{X}_1} is the population ratio of

arithmetic means for sample 2 with respect to sample 1 and

log(r_{null}) = 0 assumes the population means are identical.

When simulating data from sim_bnb(), the mean is a function of the

item (subject) random effect which in turn is a function of the dispersion

parameter. Thus, glmm_poisson() has biased mean estimates. The bias

increases as the dispersion parameter gets smaller and decreases as the

dispersion parameter gets larger. However, estimates of the ratio and

standard deviation of the random intercept tend to be accurate. In summary,

the Poisson mixed-effects model fit by glmm_poisson() is not recommended

for the BNB data simulated by sim_bnb(). Instead, wald_test_bnb() or

lrt_bnb() should typically be used instead.

Value

A list with the following elements:

| Slot | Subslot | Name | Description |

| 1 | chisq | \chi^2 test statistic for the ratio of means. |

|

| 2 | df | Degrees of freedom. | |

| 3 | p | p-value. | |

| 4 | ratio | Estimated ratio of means (sample 2 / sample 1). | |

| 4 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 4 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 4 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 5 | mean1 | Estimated mean of sample 1. | |

| 5 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 5 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 5 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 6 | mean2 | Estimated mean of sample 2. | |

| 6 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 6 | 2 | lower | Wald confidence interval lower bound. |

| 6 | 3 | upper | Wald confidence interval upper bound. |

| 7 | item_sd | Estimated standard deviation of the item (subject) random intercept. | |

| 7 | 1 | estimate | Point estimate. |

| 7 | 2 | lower | Confidence interval lower bound. |

| 7 | 3 | upper | Confidence interval upper bound. |

| 8 | n1 | Sample size of sample 1. | |

| 9 | n2 | Sample size of sample 2. | |

| 10 | method | Method used for the results. | |

| 11 | test | Type of hypothesis test. | |

| 12 | alternative | The alternative hypothesis. | |

| 13 | ci_level | Confidence level of the interval. | |

| 14 | hessian | Information about the Hessian matrix. | |

| 15 | convergence | Information about convergence. |

References

Hilbe JM (2011). Negative Binomial Regression, 2 edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521198158 9780511973420, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511973420.

Hilbe JM (2014). Modeling count data. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. ISBN 9781107028333 9781107611252, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139236065.

See Also

wald_test_bnb(),

lrt_bnb(),

glmm_bnb()

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# glmm_poisson() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

d <- sim_bnb(

n = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.2,

dispersion = 2

)

lrt <- glmm_poisson(d, test = "lrt")

lrt

wald <- glmm_poisson(d, test = "wald", ci_level = 0.95)

wald

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Compare results to manual calculation of chi-square statistic

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Use the same data, but as a data frame instead of list

set.seed(1234)

d <- sim_bnb(

n = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.2,

dispersion = 2,

return_type = "data.frame"

)

mod_alt <- glmmTMB::glmmTMB(

formula = value ~ condition + (1 | item),

data = d,

family = stats::poisson

)

mod_null <- glmmTMB::glmmTMB(

formula = value ~ 1 + (1 | item),

data = d,

family = stats::poisson

)

lrt_chisq <- as.numeric(-2 * (logLik(mod_null) - logLik(mod_alt)))

lrt_chisq

wald_chisq <- summary(mod_alt)$coefficients$cond["condition2", "z value"]^2

wald_chisq

anova(mod_null, mod_alt)

Likelihood ratio test for BNB ratio of means

Description

Likelihood ratio test for the ratio of means from bivariate negative binomial outcomes.

Usage

lrt_bnb(data, ratio_null = 1, distribution = asymptotic(), ...)

Arguments

data |

(list) |

ratio_null |

(Scalar numeric: |

distribution |

(function: |

... |

Optional arguments passed to the MLE function |

Details

This function is primarily designed for speed in simulation. Missing values are silently excluded.

Suppose X_1 \mid G = g \sim \text{Poisson}(\mu g) and

X_2 \mid G = g \sim \text{Poisson}(r \mu g) where

G \sim \text{Gamma}(\theta, \theta^{-1}) is the random item (subject)

effect. Then X_1, X_2 \sim \text{BNB}(\mu, r, \theta) is the joint

distribution where X_1 and X_2 are dependent (though conditionally

independent), X_1 is the count outcome for sample 1 of the items

(subjects), X_2 is the count outcome for sample 2 of the items (subjects),

\mu is the conditional mean of sample 1, r is the ratio of the

conditional means of sample 2 with respect to sample 1, and \theta is

the gamma distribution shape parameter which controls the dispersion and the

correlation between sample 1 and 2.

The hypotheses for the LRT of r are

\begin{aligned}

H_{null} &: r = r_{null} \\

H_{alt} &: r \neq r_{null}

\end{aligned}

where r = \frac{\bar{X}_2}{\bar{X}_1} is the population ratio of

arithmetic means for sample 2 with respect to sample 1 and r_{null} is

a constant for the assumed null population ratio of means (typically

r_{null} = 1).

The LRT statistic is

\begin{aligned}

\lambda &= -2 \ln \frac{\text{sup}_{\Theta_{null}} L(r, \mu, \theta)}{\text{sup}_{\Theta} L(r, \mu, \theta)} \\

&= -2 \left[ \ln \text{sup}_{\Theta_{null}} L(r, \mu, \theta) - \ln \text{sup}_{\Theta} L(r, \mu, \theta) \right] \\

&= -2(l(r_{null}, \tilde{\mu}, \tilde{\theta}) - l(\hat{r}, \hat{\mu}, \hat{\theta}))

\end{aligned}

Under H_{null}, the LRT test statistic is asymptotically distributed

as \chi^2_1. The approximate level \alpha test rejects

H_{null} if \lambda \geq \chi^2_1(1 - \alpha). However,

the asymptotic critical value is known to underestimate the exact critical

value and the nominal significance level may not be achieved for small sample

sizes. Argument distribution allows control of the distribution of

the \chi^2_1 test statistic under the null hypothesis by use of

functions asymptotic() and simulated().

Value

A list with the following elements:

| Slot | Subslot | Name | Description |

| 1 | chisq | \chi^2 test statistic for the ratio of means. |

|

| 2 | df | Degrees of freedom. | |

| 3 | p | p-value. | |

| 4 | ratio | Estimated ratio of means (sample 2 / sample 1). | |

| 5 | alternative | Point estimates under the alternative hypothesis. | |

| 5 | 1 | mean1 | Estimated mean of sample 1. |

| 5 | 2 | mean2 | Estimated mean of sample 2. |

| 5 | 3 | dispersion | Estimated dispersion. |

| 6 | null | Point estimates under the null hypothesis. | |

| 6 | 1 | mean1 | Estimated mean of sample 1. |

| 6 | 2 | mean2 | Estimated mean of sample 2. |

| 6 | 3 | dispersion | Estimated dispersion. |

| 7 | n1 | The sample size of sample 1. | |

| 8 | n2 | The sample size of sample 2. | |

| 9 | method | Method used for the results. | |

| 10 | ratio_null | Assumed population ratio of means. | |

| 11 | mle_code | Integer indicating why the optimization process terminated. | |

| 12 | mle_message | Information from the optimizer. |

References

Rettiganti M, Nagaraja HN (2012). “Power Analyses for Negative Binomial Models with Application to Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Trials.” Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 22(2), 237–259. ISSN 1054-3406, 1520-5711, doi:10.1080/10543406.2010.528105.

Aban IB, Cutter GR, Mavinga N (2009). “Inferences and power analysis concerning two negative binomial distributions with an application to MRI lesion counts data.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53(3), 820–833. ISSN 01679473, doi:10.1016/j.csda.2008.07.034.

See Also

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# lrt_bnb() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

sim_bnb(

n = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.2,

dispersion = 2

) |>

lrt_bnb()

Likelihood ratio test for NB ratio of means

Description

Likelihood ratio test for the ratio of means from two independent negative binomial outcomes.

Usage

lrt_nb(

data,

equal_dispersion = FALSE,

ratio_null = 1,

distribution = asymptotic(),

...

)

Arguments

data |

(list) |

equal_dispersion |

(Scalar logical: |

ratio_null |

(Scalar numeric: |

distribution |

(function: |

... |

Optional arguments passed to the MLE function |

Details

This function is primarily designed for speed in simulation. Missing values are silently excluded.

Suppose X_1 \sim NB(\mu, \theta_1) and

X_2 \sim NB(r\mu, \theta_2) where X_1 and X_2 are

independent, X_1 is the count outcome for items in group 1, X_2

is the count outcome for items in group 2, \mu is the arithmetic mean

count in group 1, r is the ratio of arithmetic means for group 2 with

respect to group 1, \theta_1 is the dispersion parameter of group 1,

and \theta_2 is the dispersion parameter of group 2.

The hypotheses for the LRT of r are

\begin{aligned}

H_{null} &: r = r_{null} \\

H_{alt} &: r \neq r_{null}

\end{aligned}

where r = \frac{\bar{X}_2}{\bar{X}_1} is the population ratio of

arithmetic means for group 2 with respect to group 1 and r_{null} is a

constant for the assumed null population ratio of means (typically

r_{null} = 1).

The LRT statistic is

\begin{aligned}

\lambda &= -2 \ln \frac{\text{sup}_{\Theta_{null}} L(r, \mu, \theta_1, \theta_2)}{\text{sup}_{\Theta} L(r, \mu, \theta_1, \theta_2)} \\

&= -2 \left[ \ln \text{sup}_{\Theta_{null}} L(r, \mu, \theta_1, \theta_2) - \ln \text{sup}_{\Theta} L(r, \mu, \theta_1, \theta_2) \right] \\

&= -2(l(r_{null}, \tilde{\mu}, \tilde{\theta}_1, \tilde{\theta}_2) - l(\hat{r}, \hat{\mu}, \hat{\theta}_1, \hat{\theta}_2))

\end{aligned}

Under H_{null}, the LRT test statistic is asymptotically distributed

as \chi^2_1. The approximate level \alpha test rejects

H_{null} if \lambda \geq \chi^2_1(1 - \alpha). However,

the asymptotic critical value is known to underestimate the exact critical

value and the nominal significance level may not be achieved for small sample

sizes. Argument distribution allows control of the distribution of

the \chi^2_1 test statistic under the null hypothesis by use of

functions asymptotic() and simulated().

Note that standalone use of this function with equal_dispersion = FALSE

and distribution = simulated(), e.g.

data |>

lrt_nb(

equal_dispersion = FALSE,

distribution = simulated()

)

results in a nonparametric randomization test based on label permutation.

This violates the assumption of exchangeability for the randomization test

because the labels are not exchangeable when the null hypothesis assumes

unequal dispersions. However, used inside power(), e.g.

data |>

power(

lrt_nb(

equal_dispersion = FALSE,

distribution = simulated()

)

)

results in parametric resampling and no label permutation is performed.

Thus, setting equal_dispersion = FALSE and distribution = simulated() is

only recommended when lrt_nb() is used inside of

power(). See also, simulated().

Value

A list with the following elements:

| Slot | Subslot | Name | Description |

| 1 | chisq | \chi^2 test statistic for the ratio of means. |

|

| 2 | df | Degrees of freedom. | |

| 3 | p | p-value. | |

| 4 | ratio | Estimated ratio of means (group 2 / group 1). | |

| 5 | alternative | Point estimates under the alternative hypothesis. | |

| 5 | 1 | mean1 | Estimated mean of group 1. |

| 5 | 2 | mean2 | Estimated mean of group 2. |

| 5 | 3 | dispersion1 | Estimated dispersion of group 1. |

| 5 | 4 | dispersion2 | Estimated dispersion of group 2. |

| 6 | null | Point estimates under the null hypothesis. | |

| 6 | 1 | mean1 | Estimated mean of group 1. |

| 6 | 2 | mean2 | Estimated mean of group 2. |

| 6 | 3 | dispersion1 | Estimated dispersion of group 1. |

| 6 | 4 | dispersion2 | Estimated dispersion of group 2. |

| 7 | n1 | Sample size of group 1. | |

| 8 | n2 | Sample size of group 2. | |

| 9 | method | Method used for the results. | |

| 10 | equal_dispersion | Whether or not equal dispersions were assumed. | |

| 11 | ratio_null | Assumed population ratio of means. | |

| 12 | mle_code | Integer indicating why the optimization process terminated. | |

| 13 | mle_message | Information from the optimizer. |

References

Rettiganti M, Nagaraja HN (2012). “Power Analyses for Negative Binomial Models with Application to Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Trials.” Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 22(2), 237–259. ISSN 1054-3406, 1520-5711, doi:10.1080/10543406.2010.528105.

Aban IB, Cutter GR, Mavinga N (2009). “Inferences and power analysis concerning two negative binomial distributions with an application to MRI lesion counts data.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53(3), 820–833. ISSN 01679473, doi:10.1016/j.csda.2008.07.034.

See Also

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# lrt_nb() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

sim_nb(

n1 = 60,

n2 = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.5,

dispersion1 = 2,

dispersion2 = 8

) |>

lrt_nb()

MLE for BNB

Description

Maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) for bivariate negative binomial outcomes.

Usage

mle_bnb_null(data, ratio_null = 1, method = "nlm_constrained", ...)

mle_bnb_alt(data, method = "nlm_constrained", ...)

Arguments

data |

(list) |

ratio_null |

(Scalar numeric: |

method |

(string: |

... |

Optional arguments passed to the optimization method. |

Details

These functions are primarily designed for speed in simulation. Missing values are silently excluded.

Suppose X_1 \mid G = g \sim \text{Poisson}(\mu g) and

X_2 \mid G = g \sim \text{Poisson}(r \mu g) where

G \sim \text{Gamma}(\theta, \theta^{-1}) is the random item (subject) effect.

Then X_1, X_2 \sim \text{BNB}(\mu, r, \theta) is the joint distribution where

X_1 and X_2 are dependent (though conditionally independent),

X_1 is the count outcome for sample 1 of the items (subjects),

X_2 is the count outcome for sample 2 of the items (subjects),

\mu is the conditional mean of sample 1, r is the ratio of the

conditional means of sample 2 with respect to sample 1, and \theta is

the gamma distribution shape parameter which controls the dispersion and the

correlation between sample 1 and 2.

The MLEs of r and \mu are \hat{r} = \frac{\bar{x}_2}{\bar{x}_1}

and \hat{\mu} = \bar{x}_1. The MLE of \theta is found by

maximizing the profile log-likelihood

l(\hat{r}, \hat{\mu}, \theta) with respect to \theta. When

r = r_{null} is known, the MLE of \mu is

\tilde{\mu} = \frac{\bar{x}_1 + \bar{x}_2}{1 + r_{null}} and

\tilde{\theta} is obtained by maximizing the profile log-likelihood

l(r_{null}, \tilde{\mu}, \theta) with respect to \theta.

The backend method for numerical optimization is controlled by argument

method which refers to stats::nlm(), stats::nlminb(), or

stats::optim(). If you would like to see warnings from the optimizer,

include argument warnings = TRUE.

Value

For

mle_bnb_alt, a list with the following elements:Slot Name Description 1 mean1MLE for mean of sample 1. 2 mean2MLE for mean of sample 2. 3 ratioMLE for ratio of means. 4 dispersionMLE for BNB dispersion. 5 nllMinimum of negative log-likelihood. 6 nparamsNumber of estimated parameters. 7 n1Sample size of sample 1. 8 n2Sample size of sample 2. 9 methodMethod used for the results. 10 mle_methodMethod used for optimization. 11 mle_codeInteger indicating why the optimization process terminated. 12 mle_messageAdditional information from the optimizer. For

mle_bnb_null, a list with the following elements:Slot Name Description 1 mean1MLE for mean of sample 1. 2 mean2MLE for mean of sample 2. 3 ratio_nullPopulation ratio of means assumed for null hypothesis. mean2 = mean1 * ratio_null.4 dispersionMLE for BNB dispersion. 5 nllMinimum of negative log-likelihood. 6 nparamsNumber of estimated parameters. 7 n1Sample size of sample 1. 8 n2Sample size of sample 2. 9 methodMethod used for the results. 10 mle_methodMethod used for optimization. 11 mle_codeInteger indicating why the optimization process terminated. 12 mle_messageAdditional information from the optimizer.

References

Rettiganti M, Nagaraja HN (2012). “Power Analyses for Negative Binomial Models with Application to Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Trials.” Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 22(2), 237–259. ISSN 1054-3406, 1520-5711, doi:10.1080/10543406.2010.528105.

Aban IB, Cutter GR, Mavinga N (2009). “Inferences and power analysis concerning two negative binomial distributions with an application to MRI lesion counts data.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53(3), 820–833. ISSN 01679473, doi:10.1016/j.csda.2008.07.034.

See Also

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# mle_bnb() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

d <- sim_bnb(

n = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.2,

dispersion = 2

)

mle_alt <- d |>

mle_bnb_alt()

mle_null <- d |>

mle_bnb_null()

mle_alt

mle_null

MLE for NB

Description

Maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) for two independent negative binomial outcomes.

Usage

mle_nb_null(

data,

equal_dispersion = FALSE,

ratio_null = 1,

method = "nlm_constrained",

...

)

mle_nb_alt(data, equal_dispersion = FALSE, method = "nlm_constrained", ...)

Arguments

data |

(list) |

equal_dispersion |

(Scalar logical: |

ratio_null |

(Scalar numeric: |

method |

(string: |

... |

Optional arguments passed to the optimization method. |

Details

These functions are primarily designed for speed in simulation. Missing values are silently excluded.

Suppose X_1 \sim \text{NB}(\mu, \theta_1) and

X_2 \sim \text{NB}(r\mu, \theta_2), where X_1 and X_2 are

independent, X_1 is the count outcome for items in group 1, X_2

is the count outcome for items in group 2, \mu is the arithmetic mean

count in group 1, r is the ratio of arithmetic means for group 2 with

respect to group 1, \theta_1 is the dispersion parameter of group 1,

and \theta_2 is the dispersion parameter of group 2.

The MLEs of r and \mu are \hat{r} = \frac{\bar{x}_2}{\bar{x}_1}

and \hat{\mu} = \bar{x}_1. The MLEs of \theta_1 and \theta_2

are found by maximizing the profile log-likelihood

l(\hat{r}, \hat{\mu}, \theta_1, \theta_2) with respect to

\theta_1 and \theta_2. When r = r_{null} is known, the MLE

of \mu is

\tilde{\mu} = \frac{n_1 \bar{x}_1 + n_2 \bar{x}_2}{n_1 + n_2} and

\tilde{\theta}_1 and \tilde{\theta}_2 are obtained by maximizing

the profile log-likelihood l(r_{null}, \tilde{\mu}, \theta_1, \theta_2).

The backend method for numerical optimization is controlled by argument

method which refers to stats::nlm(), stats::nlminb(), or

stats::optim(). If you would like to see warnings from the optimizer,

include argument warnings = TRUE.

Value

For

mle_nb_alt(), a list with the following elements:Slot Name Description 1 mean1MLE for mean of group 1. 2 mean2MLE for mean of group 2. 3 ratioMLE for ratio of means. 4 dispersion1MLE for dispersion of group 1. 5 dispersion2MLE for dispersion of group 2. 6 equal_dispersionWere equal dispersions assumed. 7 n1Sample size of group 1. 8 n2Sample size of group 2. 9 nllMinimum of negative log-likelihood. 10 nparamsNumber of estimated parameters. 11 methodMethod used for the results. 12 mle_methodMethod used for optimization. 13 mle_codeInteger indicating why the optimization process terminated. 14 mle_messageAdditional information from the optimizer. For

mle_nb_null(), a list with the following elements:Slot Name Description 1 mean1MLE for mean of group 1. 2 mean2MLE for mean of group 2. 3 ratio_nullPopulation ratio of means assumed for null hypothesis. mean2 = mean1 * ratio_null.4 dispersion1MLE for dispersion of group 1. 5 dispersion2MLE for dispersion of group 2. 6 equal_dispersionWere equal dispersions assumed. 7 n1Sample size of group 1. 8 n2Sample size of group 2. 9 nllMinimum of negative log-likelihood. 10 nparamsNumber of estimated parameters. 11 methodMethod used for the results. 12 mle_methodMethod used for optimization. 13 mle_codeInteger indicating why the optimization process terminated. 14 mle_messageAdditional information from the optimizer.

References

Rettiganti M, Nagaraja HN (2012). “Power Analyses for Negative Binomial Models with Application to Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Trials.” Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 22(2), 237–259. ISSN 1054-3406, 1520-5711, doi:10.1080/10543406.2010.528105.

Aban IB, Cutter GR, Mavinga N (2009). “Inferences and power analysis concerning two negative binomial distributions with an application to MRI lesion counts data.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53(3), 820–833. ISSN 01679473, doi:10.1016/j.csda.2008.07.034.

See Also

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# mle_nb() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

d <- sim_nb(

n1 = 60,

n2 = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.5,

dispersion1 = 2,

dispersion2 = 8

)

mle_alt <- d |>

mle_nb_alt()

mle_null <- d |>

mle_nb_null()

mle_alt

mle_null

Negative log-likelihood for BNB

Description

The negative log-likelihood for bivariate negative binomial outcomes.

Usage

nll_bnb_null(param, value1, value2, ratio_null)

nll_bnb_alt(param, value1, value2)

Arguments

param |

(numeric:

for samples 1 and 2. |

value1 |

(integer: |

value2 |

(integer: |

ratio_null |

(Scalar numeric: |

Details

These functions are primarily designed for speed in simulation. Limited argument validation is performed.

Suppose X_1 \mid G = g \sim \text{Poisson}(\mu g) and

X_2 \mid G = g \sim \text{Poisson}(r \mu g) where

G \sim \text{Gamma}(\theta, \theta^{-1}) is the random item (subject) effect.

Then X_1, X_2 \sim \text{BNB}(\mu, r, \theta) is the joint distribution where

X_1 and X_2 are dependent (though conditionally independent),

X_1 is the count outcome for sample 1 of the items (subjects),

X_2 is the count outcome for sample 2 of the items (subjects),

\mu is the conditional mean of sample 1, r is the ratio of the

conditional means of sample 2 with respect to sample 1, and \theta is

the gamma distribution shape parameter which controls the dispersion and the

correlation between sample 1 and 2.

The likelihood is

\begin{aligned}

L(r, \mu, \theta \mid X_1, X_2) = & \left( \frac{\theta^{\theta}}{\Gamma(\theta)} \right)^{n} \times \\

& \frac{\mu^{\sum{x_{1i}} + \sum{x_{2i}}}}{\prod_{i=1}^{n} x_{1i}!} \frac{r^{\sum{x_{2i}}}}{\prod_{i=1}^{n} x_{2i}!} \times \\

& \frac{\prod_{i = 1}^{n} \Gamma(x_{1i} + x_{2i} + \theta)}{(\mu + r \mu + \theta)^{\sum (x_{1i} + x_{2i} + \theta)}}

\end{aligned}

and the parameter space is

\Theta = \left\{ (r, \mu, \theta) : r, \mu, \theta > 0 \right\}.

The log-likelihood is

\begin{aligned}

l(r, \mu, \theta) = \ & n \left[ \theta \ln \theta - \ln \Gamma(\theta) \right] + \\

& n (\bar{x}_1 + \bar{x}_2) \ln(\mu) + n \bar{x}_2 \ln r + \\

& \sum_{i=1}^{n}{\ln \Gamma(x_{1i} + x_{2i} + \theta)} - \\

& n (\bar{x}_1 + \bar{x}_2 + \theta) \ln(\mu + r\mu + \theta) - \\

& \sum_{i = 1}^{n}{\ln x_{1i}!} - \sum_{i = 1}^{n}{\ln x_{2i}!}

\end{aligned}

Value

Scalar numeric negative log-likelihood.

References

Rettiganti M, Nagaraja HN (2012). “Power Analyses for Negative Binomial Models with Application to Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Trials.” Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 22(2), 237–259. ISSN 1054-3406, 1520-5711, doi:10.1080/10543406.2010.528105.

Aban IB, Cutter GR, Mavinga N (2009). “Inferences and power analysis concerning two negative binomial distributions with an application to MRI lesion counts data.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53(3), 820–833. ISSN 01679473, doi:10.1016/j.csda.2008.07.034.

See Also

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# nll_bnb*() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

d <- sim_bnb(

n = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.2,

dispersion = 2

)

nll_bnb_alt(

param = c(mean1 = 10, mean2 = 12, dispersion = 2),

value1 = d[[1L]],

value2 = d[[2L]]

)

nll_bnb_null(

param = c(mean = 10, dispersion = 2),

value1 = d[[1L]],

value2 = d[[2L]],

ratio_null = 1

)

Negative log-likelihood for NB

Description

The negative log-likelihood for two independent samples of negative binomial distributions.

Usage

nll_nb_null(param, value1, value2, equal_dispersion, ratio_null)

nll_nb_alt(param, value1, value2, equal_dispersion)

Arguments

param |

(numeric:

for groups 1 and 2. |

value1 |

(integer: |

value2 |

(integer: |

equal_dispersion |

(Scalar logical) |

ratio_null |

(Scalar numeric: |

Details

These functions are primarily designed for speed in simulation. Limited argument validation is performed.

Suppose X_1 \sim \text{NB}(\mu, \theta_1) and

X_2 \sim \text{NB}(r\mu, \theta_2) where X_1 and X_2 are

independent, X_1 is the count outcome for items in group 1, X_2

is the count outcome for items in group 2, \mu is the arithmetic mean

count in group 1, r is the ratio of arithmetic means for group 2 with

respect to group 1, \theta_1 is the dispersion parameter of group 1,

and \theta_2 is the dispersion parameter of group 2.

Unequal dispersion parameters

When the dispersion parameters are not equal, the likelihood is

\begin{aligned}

L(r, \mu, \theta_1, \theta_2 \mid X_1, X_2) = & \left( \frac{\theta_1^{\theta_1}}{\Gamma(\theta_1)} \right)^{n_1} \frac{\mu^{\sum{x_{1i}}}}{(\mu + \theta_1)^{\sum{x_{1i} + n_1 \theta_1}}} \times \\

& \left( \frac{\theta_2^{\theta_2}}{\Gamma(\theta_2)} \right)^{n_2} \frac{(r \mu)^{\sum{x_{2j}}}}{(r \mu + \theta_2)^{\sum{x_{2j} + n_2 \theta_2}}} \times \\

& \prod_{i = 1}^{n_1}{\frac{\Gamma(x_{1i} + \theta_1)}{x_{1i}!}} \prod_{j = 1}^{n_2}{\frac{\Gamma(x_{2j} + \theta_2)}{x_{2j}!}}

\end{aligned}

and the parameter space is

\Theta = \left\{ (r, \mu, \theta_1, \theta_2) : r, \mu, \theta_1, \theta_2 > 0 \right\}.

The log-likelihood is

\begin{aligned}

l(r, \mu, \theta_1, \theta_2) = \ &n_1 \left[ \theta_1 \ln \theta_1 - \ln \Gamma(\theta_1) \right] + \\

&n_2 \left[ \theta_2 \ln \theta_2 - \ln \Gamma(\theta_2) \right] + \\

&(n_1 \bar{x}_1 + n_2 \bar{x}_2) \ln(\mu) - n_1 (\bar{x}_1 + \theta_1) \ln(\mu + \theta_1) + \\

&n_2 \bar{x}_2 \ln(r) - n_2 (\bar{x}_2 + \theta_2) \ln(r \mu + \theta_2) + \\

&\sum_{i = 1}^{n_1}{\left( \ln \Gamma(x_{1i} + \theta_1) - \ln(x_{1i}!) \right)} + \\

&\sum_{j = 1}^{n_2}{\left( \ln \Gamma(x_{2j} + \theta_2) - \ln(x_{2j}!) \right)}

\end{aligned}

Equal dispersion parameters

When the dispersion parameters are equal, the likelihood is

\begin{aligned}

L(r, \mu, \theta \mid X_1, X_2) = & \left( \frac{\theta^{\theta}}{\Gamma(\theta)} \right)^{n_1 + n_2} \times \\

& \frac{\mu^{\sum{x_{1i}}}}{(\mu + \theta)^{\sum{x_{1i} + n_1 \theta}}} \frac{(r \mu)^{\sum{x_{2j}}}}{(r \mu + \theta)^{\sum{x_{2j} + n_2 \theta}}} \times \\

& \prod_{i = 1}^{n_1}{\frac{\Gamma(x_{1i} + \theta)}{x_{1i}!}} \prod_{j = 1}^{n_2}{\frac{\Gamma(x_{2j} + \theta)}{x_{2j}!}}

\end{aligned}

and the parameter space is

\Theta = \left\{ (r, \mu, \theta) : r, \mu, \theta > 0 \right\}.

The log-likelihood is

\begin{aligned}

l(r, \mu, \theta) = \ &(n_1 + n_2) \left[ \theta \ln \theta - \ln \Gamma(\theta) \right] + \\

&(n_1 \bar{x}_1 + n_2 \bar{x}_2) \ln(\mu) - n_1 (\bar{x}_1 + \theta) \ln(\mu + \theta) + \\

&n_2 \bar{x}_2 \ln(r) - n_2 (\bar{x}_2 + \theta) \ln(r \mu + \theta) + \\

&\sum_{i = 1}^{n_1}{\left( \ln \Gamma(x_{1i} + \theta) - \ln(x_{1i}!) \right)} + \\

&\sum_{j = 1}^{n_2}{\left( \ln \Gamma(x_{2j} + \theta) - \ln(x_{2j}!) \right)}

\end{aligned}

Value

Scalar numeric negative log-likelihood.

References

Rettiganti M, Nagaraja HN (2012). “Power Analyses for Negative Binomial Models with Application to Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Trials.” Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 22(2), 237–259. ISSN 1054-3406, 1520-5711, doi:10.1080/10543406.2010.528105.

Aban IB, Cutter GR, Mavinga N (2009). “Inferences and power analysis concerning two negative binomial distributions with an application to MRI lesion counts data.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53(3), 820–833. ISSN 01679473, doi:10.1016/j.csda.2008.07.034.

See Also

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# nll_nb_*() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

set.seed(1234)

d <- sim_nb(

n1 = 60,

n2 = 40,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = 1.5,

dispersion1 = 2,

dispersion2 = 8

)

nll_nb_alt(

param = c(mean1 = 10, mean2 = 15, dispersion1 = 2, dispersion2 = 8),

value1 = d[[1L]],

value2 = d[[2L]],

equal_dispersion = FALSE

)

nll_nb_null(

param = c(mean = 10, dispersion1 = 2, dispersion2 = 8),

value1 = d[[1L]],

value2 = d[[2L]],

equal_dispersion = FALSE,

ratio_null = 1

)

Plot power objects

Description

An automatic plot method for objects returned by power().

Usage

## S3 method for class 'depower'

plot(

x,

x_axis = NULL,

y_axis = NULL,

color = NULL,

facet_row = NULL,

facet_col = NULL,

hline = NULL,

caption = TRUE,

caption_width = 70L,

...

)

Arguments

x |

(depower) |

x_axis |

(string: |

y_axis |

(string: |

color |

(string: |

facet_row |

(string: |

facet_col |

(string: |

hline |

(numeric: |

caption |

(Scalar logical: |

caption_width |

(Scalar integer: |

... |

Unused additional arguments. |

Details

If you are limited by the output from plot.depower(), keep in mind that the

object returned by power() is a standard data frame. This allows

you to easily plot all results with standard plotting functions. In addition,

because plot.depower() uses ggplot2, you can modify the plot as you

normally would. For example:

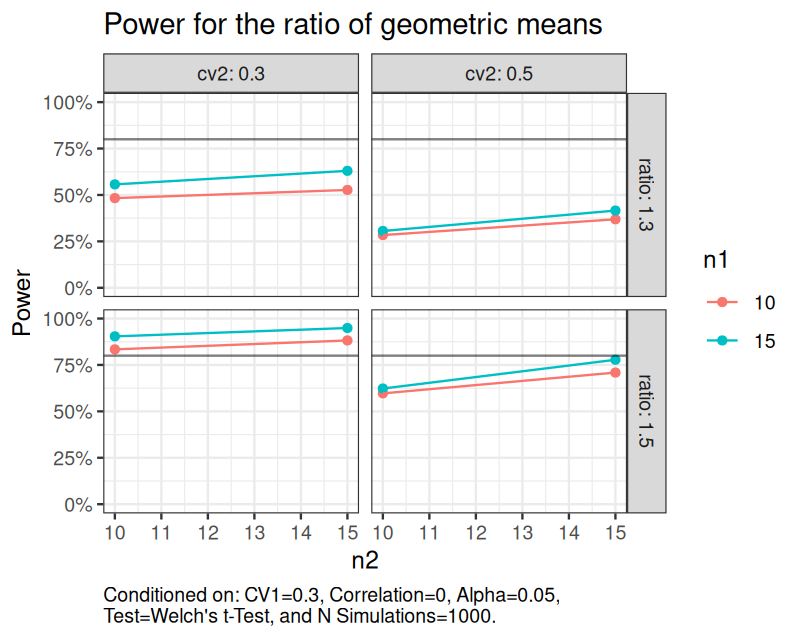

set.seed(1234) sim_log_lognormal( n1 = c(10, 15), n2 = c(10, 15), ratio = c(1.3, 1.5), cv1 = c(0.3), cv2 = c(0.3, 0.5), nsims = 1000 ) |> power(alpha = 0.05) |> plot(hline = 0.8, caption_width = 60) + ggplot2::theme_bw() + ggplot2::theme(plot.caption = ggplot2::element_text(hjust = 0)) + ggplot2::labs(title = "Power for the ratio of geometric means")

Value

A ggplot2::ggplot() object.

See Also

Examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# plot() examples

#----------------------------------------------------------------------------

library(depower)

# Power for independent two-sample t-test

# Includes shaded region for Bayesian poster predictive interval which

# summarizes the plausible range of power estimates for a future simulation

# study based on 500 data simulations.

set.seed(1234)

sim_log_lognormal(

n1 = c(10, 15),

n2 = c(10, 15),

ratio = c(1.3, 1.5),

cv1 = c(0.3),

cv2 = c(0.3, 0.5),

nsims = 500

) |>

power(alpha = 0.05) |>

add_power_pi() |>

plot()

# Power for dependent two-sample t-test

set.seed(1234)

sim_log_lognormal(

n1 = c(10, 15),

n2 = c(10, 15),

ratio = c(1.3, 1.5),

cv1 = c(0.3, 0.5),

cv2 = c(0.3, 0.5),

cor = c(0.3),

nsims = 500

) |>

power(alpha = 0.01) |>

plot()

# Power for two-sample independent AND two-sample dependent t-test

set.seed(1234)

sim_log_lognormal(

n1 = c(10, 15),

n2 = c(10, 15),

ratio = c(1.3, 1.5),

cv1 = c(0.3),

cv2 = c(0.3),

cor = c(0, 0.3, 0.6),

nsims = 500

) |>

power(alpha = c(0.05, 0.01)) |>

plot(facet_row = "cor", color = "test")

# Power for one-sample t-test

set.seed(1234)

sim_log_lognormal(

n1 = c(10, 15),

ratio = c(1.2, 1.4),

cv1 = c(0.3, 0.5),

nsims = 500

) |>

power(alpha = c(0.05, 0.01)) |>

plot()

# Power for independent two-sample NB test

set.seed(1234)

sim_nb(

n1 = c(10, 15),

mean1 = 10,

ratio = c(1.8, 2),

dispersion1 = 10,

dispersion2 = 3,

nsims = 100

) |>

power(alpha = 0.01) |>

plot()

# Power for BNB test

set.seed(1234)

sim_bnb(

n = c(10, 12),

mean1 = 10,

ratio = c(1.3, 1.5),

dispersion = 5,

nsims = 100

) |>

power(alpha = 0.01) |>

plot()

Simulated power

Description

A method to calculate power for objects returned by sim_log_lognormal(),

sim_nb(), and sim_bnb().

Usage

power(data, ..., alpha = 0.05, list_column = FALSE, ncores = 1L)

Arguments

data |

(depower) |

... |

(functions) |

alpha |

(numeric: |

list_column |

(Scalar logical: |

ncores |

(Scalar integer: |

Details

Power is calculated as the proportion of hypothesis tests which result in a

p-value less than or equal to alpha. e.g.

sum(p <= alpha) / nsims

Power is defined as the expected probability of rejecting the null hypothesis for a chosen value of the unknown effect. In a multiple comparisons scenario, power is defined as the marginal power, which is the expected power of the test for each individual null hypothesis assumed to be false.

Other forms of power under the multiple comparisons scenario include

disjunctive or conjunctive power. Disjunctive power is defined as the

expected probability of correctly rejecting one or more null hypotheses.

Conjunctive power is defined as the expected probability of correctly

rejecting all null hypotheses. In the simplest case, and where all hypotheses

are independent, if the marginal power is defined as \pi and m is

the number of null hypotheses assumed to be false, then disjunctive power may

be calculated as 1 - (1 - \pi)^m and conjunctive power may be calculated

as \pi^m. Disjunctive power tends to decrease with increasingly

correlated hypotheses and conjunctive power tends to increase with

increasingly correlated hypotheses.

Argument ...

... are the name-value pairs for the functions used to perform the tests.

If not named, the functions coerced to character will be used for the

name-value pairs. Typical in non-standard evaluation, ... accepts bare

functions and converts them to a list of expressions. Each element in this

list will be validated as a call and then evaluated on the simulated data.

A base::call() is simply an unevaluated function. Below are some examples

of specifying ... in power().

# Examples of specifying ... in power()

data <- sim_nb(

n1 = 10,

mean1 = 10,

ratio = c(1.6, 2),

dispersion1 = 2,

dispersion2 = 2,

nsims = 200

)

# ... is empty, so an appropriate default function will be provided

power(data)

# This is equivalent to leaving ... empty

power(data, "NB Wald test" = wald_test_nb())

# If not named, "wald_test_nb()" will be used to label the function

power(data, wald_test_nb())

# You can specify any parameters in the call. The data argument

# will automatically be inserted or overwritten.

data |>

power("NB Wald test" = wald_test_nb(equal_dispersion=TRUE, link="log"))

# Multiple functions may be used.

data |>

power(

wald_test_nb(link='log'),

wald_test_nb(link='sqrt'),

wald_test_nb(link='squared'),

wald_test_nb(link='identity')

)

# Just like functions in a pipe, the parentheses are required.

# This will error because wald_test_nb is missing parentheses.

try(power(data, wald_test_nb))

In most cases*, any user created test function may be utilized in ... if the

following conditions are satisfied:

The function contains argument

datawhich is defined as a list with the first and second elements for simulated data.The return object is a list with element

pfor the p-value of the hypothesis test.

Validate with test cases beforehand.

*Simulated data of class log_lognormal_mixed_two_sample has both independent

and dependent data. To ensure the appropriate test function is used,

power.log_lognormal_mixed_two_sample() allows only

t_test_welch() and t_test_paired() in .... Each will

be evaluated on the simulated data according to column data$cor. If one or

both of these functions are not included in ..., the corresponding default

function will be used automatically. If any other test function is included,